Regional growth, Labour and the biggest decisions still to come

Reflections on National Productivity Week 2025

Reflections on National Productivity Week 2025

ANDY WESTWOOD

When Rachel Reeves gave her recent speech on kickstarting growth, she committed the Labour government to supporting a third runway at Heathrow, a renewed ‘OxCam corridor’ and the long delayed Lower Thames Crossing. Largely all initiatives that previous governments had promised but either failed to deliver or had lost interest in. But each has now become totemic to Labour’s commitment to economic growth and persuading the private sector that this is a long term approach (the nature of the overall model – or theory – of growth has been ably discussed by Ben Ansell).

However, as many observers have quickly pointed out, it’s not clear what this means for the many (largely poorer) cities and regions outside of London and the South East. Few might have expected ‘levelling up’ – either the language or the policy framework – to remain after Labour’s election victory last summer. But beyond Labour’s manifesto promises of ‘giving back control’ and ‘deepening’ and ‘widening’ devolution, more might have expected equally ambitious plans for delivering regional economic growth.

There doesn’t seem to be a lack of will, even if the means currently feel unclear. But it hasn’t always been this way. When in opposition Rachel Reeves gave her big economics speech in Washington in May 2023, her plan had been a UK version of the US industrial policy and ‘modern supply side economics’ forged by Joe Biden and Janet Yellen. Securonomics – as it was then called – consciously drew together the ‘place based’ industrial policies of the Chips and Science, Infrastructure and Inflation Reduction Acts with Labour’s prior commitment to spending £28bn a year on its Green New Deal. It also acknowledged that the economy should be better distributed and not driven by the ‘misconceived view that a few dynamic cities and a few successful industries are all a nation needs to thrive’. Finally, it stressed the importance of security – both at a national level through defence spending or energy security (Russia had at that point only recently invaded Ukraine) and also for households and individuals wanting to feel more economically secure in their own day-to-day lives. Given the current geopolitical crisis sparked by Donald Trump and JD Vance’s comments on Europe, Russia and Ukraine, the role of defence spending both nationally and in the regions is likely to become an even more important element.

Taken all together, this approach in both the US and, in time, the UK could then address the ‘hollowing out of our industrial strength and a tragic waste of human potential across vast swathes our country’, and at the same time ‘build the industries and create the jobs of the future in the industrial heartlands of the past.’ Labour’s Green Prosperity Plan, an initiative first announced 18 months beforehand, promised investment in these industries and places. Together with the National Wealth Fund and GB Energy, Reeves promised to ‘use public investment to underpin and unlock further private investment, just as the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act have done.’

Policy shifts, industrial strategy challenges, and devolution

There have been several significant shifts since 2023. Reeves and Labour are now in government and Biden, Yellen and Jake Sullivan feel long gone. No one is talking much about a ‘new Washington consensus’ or at least not that one. Even before winning the UK General Election, Reeves and Labour had scaled back their green prosperity plan and the spending attached to it. Once in government, fiscal pressures have mounted very quickly and beyond the initial declaration of a ‘black hole’.

Having been in HM Treasury for several months, Reeves as Chancellor also describes a more familiar approach ‘to grow the supply side of the economy’. That might sound similar to ‘modern supply side economics’, but it is quite different. So even though some commitments to industrial strategy, net zero and wealth funds remain in place, we still don’t know exactly what the first will do for prioritised sub-sectors and what or where specific projects that will be backed by the latter.

As a consequence, place-based policy has – so far at least – tended to concentrate on what’s been left over. For now that has been a focus on completing the map of devolution, the building of new mayoral combined authorities and wider local government reform so that more councils are operating at greater scale – either through new combined (now strategic) authorities and/or via unitary status.

But there has been no dramatic extension of powers for the most advanced city regions (i.e. those deemed most important to driving our national economy). Neither have these mayors and authorities found the co-ordination with Whitehall departments as straightforward as they might have hoped – a sense echoed in our Productivity Forums as they discussed progress during our recent National Productivity Week. So far then this is inconsistent with an industrial strategy that identifies tackling the underperformance of the eight largest cities outside London as ‘key to raising economic growth and reducing inequality’ with a total gap – or potential contribution of some £47 billion. Of course, this is why Treasury-led devolution up to now has been concentrated on the places most likely to make such contributions – both locally and nationally.

There is a further inconsistency in that the singling out of OxCam for growth rather cuts across this ‘map’ – with only one MCA in place at one end (Cambridge and East of England) and a bit of a mess elsewhere (not exactly giving confidence that institutions or devolution are going to be the most important factor for economic growth). Yet ministers are still insisting that growth and living standards will be felt everywhere. As Rachel Reeves said just before the Autumn Budget, ‘revitalising the country’s industrial heartlands and creating decent, well-paid jobs is at the heart of our mission.’ And for the economy as a whole she is clear that it is greater investment that must ‘reignite Britain’s industrial heartlands to create good jobs in the industries of the future’.

That will be wishful thinking unless there are more concrete plans for how to they are going to achieve it. Promises of ‘green book’ reform and current models of devolution are unlikely to be sufficient. Nor is deregulation or planning reform – there simply aren’t yet the levels of private sector investment (or potential borrowing on the markets) of the scale that many cities and regions need – see research by Michiel Daams, Philip McCann, Paolo Veneri and Richard Barkham for The Productivity Institute. This is much more likely in London and nearby parts of the South East, including in the OxCam corridor, or for infrastructure – e.g. the new runways, train lines and bridges around London. But elsewhere it’s much less apparent and the government’s financial position (together with its fiscal rules and tax decisions) mean it’s unlikely to be able to afford to step in, match fund and/or de-risk private investment in other poorer parts of the country.

All of this means that it will be harder to get transformational projects off the ground. The failure to get AstraZeneca to commit to a manufacturing facility in Speke is one example. It was so nearly something that could have demonstrated how Labour’s original approach might have worked. But it wasn’t to be. Perhaps because government simply didn’t offer as much to AstraZeneca as others including Singapore? Or perhaps because it doesn’t yet know what its industrial strategy offer to such firms and places is and there isn’t yet the required ‘joining up’ between different levels of government? Eventually there might have been some £78 million of grants and R&D support on the table, even if the new Labour administration had reportedly tried to halve the size of the overall package during initial renegotiations. But it’s not yet clear how either the industrial strategy or devolved institutions might better deliver or co-ordinate research and development, skills or infrastructure policy in sufficient detail to persuade companies like AstraZeneca to commit to similar projects. Government hopes there will be more opportunities to get this right.

This all matters because it is through projects like these where the rubber will really hit the road – industrial policy has to happen and have impacts somewhere. It means that there are still lessons to be learned from the place-based industrial policies that made up Bidenomics, as well as from other countries, including in the EU. Dial-shifting projects that encourage investment, create decent jobs whether in construction or factories require more active government – including in co-ordination, institutional capacity building, effective and sustained industrial policies – and in some places, governments able to invest and sufficiently de-risk or compensate private investors and markets (that all have their own versions of the green book calculating potential profits from any investment).

Tailored regional growth strategies and bridging spatial inequality

There is a need for different approaches to deliver growth throughout the country. Put more simply, what works for Cambridge or London is not the same as in Liverpool or Leeds. Exactly the same issue applies when thinking about the different policy interventions in the Midwest compared to the tech clusters and superstar cities on the US East or West Coasts or for East and West Germany. Willing the creation of good jobs and improved living standards throughout any of these countries is an important aim but requires quite different strategies in practice.

Crucially this will involve political economy as well as regional or national growth theory. Political scientists Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker have described the emergence of ‘two Englands’ and the growing social and economic differences between the South East and the rest of the country. Half of the population of the UK, according to Philip McCann, live in places poorer than Mississippi. Janan Ganesh writing in the FT, described the ‘long run threat to nationhood from productive, outward facing regions that look at their domestic stragglers and feel – to steal a phrase – shackled to a corpse’. As he went on to warn, ‘the material gap between cities and deindustrialised heartlands has grown over decades to become the most troublesome fault-line in western democracies.’

So as Jen Williams has put it in the FT, the Labour Government really does needs a theory of growth for the North. And, like Tom Forth, I’m happy (as a West Midlander) to include the vast majority of the Midlands in that assessment and of course those in other English regions as well as in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland may feel similar. But once that becomes clearer to government, the bigger question is exactly what it might be. At The Productivity Institute we have found that strong institutions matter at all spatial levels of government (a point also emphasised by Reeves in her Mais Lecture) and that co-ordination between them is critical. A good foundation of public services and infrastructure matters everywhere, as does innovation and the availability of workforce skills to absorb and deploy new technologies and inventions. This echoes the broader base of ‘capitals’ that are necessary – as set out by the Bennett Institute and adapted into the Levelling up ‘six capitals’ framework.

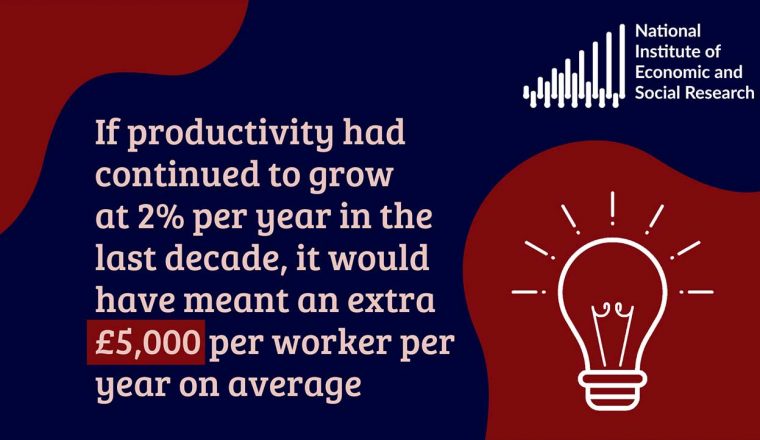

Investment in each of these things matter too of course and over the long term. Then there is the need to both speed and scale up interventions – especially in the less well performing regions – as we have recommended in our recent Regional Productivity Agenda, which we published during National Productivity Week. As critical is the realisation that, in an economy marked by such deep and enduring spatial inequality, each of these things will require more effort from government in some places than in others.

The political challenge of delivering growth

My office is in a building on The University of Manchester campus named after the economist Arthur Lewis – that’s where I sat down recently to watch the speech that Rachel Reeves gave from Oxfordshire. (There’s also a building at the LSE named after him – coincidentally where John Van Reenen and Anna Valero, both now advising Rachel Reeves at the Treasury, have been based). Lewis won a Nobel prize for his dual sector model, recognising that labour flows from less to more productive sectors and regions can provide an engine of economic growth for an economy. But we also need twin strategies to drive convergence and overall economic development in developing countries. Germany realised that as they reunified and the European Union has been following a similar path to underperforming regions and to accession countries, particularly as they expanded membership to the South and East. All are long term processes and require sustained investment from both the public and private purse.

But of course, this isn’t just about the need for a “theory of growth” outside of London and the South East, it’s the need for political strategy too. The people and places that voted Labour in 2024 need to see some tangible evidence that there has been a benefit of doing so. That might be through increased incomes, good jobs or better standards of living or it might be through steadily improving public services – health services where you can get seen by a GP, where there are buses and trains that work and local government that functions.

Taking a look at all of the different speeches that Rachel Reeves has delivered in the last few years – from Washington and Mais to the more recent one in Oxfordshire this year – it’s evident that nothing I’ve written here will come as a surprise. Indeed, ‘securonomics’ and its emphasis on national security and defence may be even more relevant today. But the outstanding question is to what extent the Chancellor is able to make good on her promise to boost growth and living standards everywhere. To that end most of the difficult choices, decisions and trade offs as well as the search for overall political and strategic coherence, still lie ahead.

Andy Westwood is Professor in Public Policy, Government and Business at the Alliance Manchester Business School and Policy Director of The Productivity Institute.