A one-stop shop for timely, comprehensive and internationally comparable global income and productivity data

How have average incomes, productivity and economic growth evolved over the last decades across the globe, and what are the latest trends? Which lower income economies have been catching up with richer ones and which ones haven’t? What are the drivers behind labour productivity growth? It are those questions that The Conference Board’s Total Economy Database (TED) is uniquely positioned to address. The database, which was originally developed by the Groningen Growth and Development Centre in the 1990s as the contemporary component of Angus Maddison’s World Economy database and the subsequent Maddison Project Database, includes annual data covering GDP, population, employment, hours, labour quality, capital services, labour productivity, and Total Factor Productivity (TFP) for 130 economies. The database is publicly available and covers 99 percent of world GDP and 97 percent of the world population. 1, 2

The uniqueness of TED is that the data are timely, comprehensive and comparable across economies (and time). It is timely in that it is released every year, usually in April, with forecasts for the running year in which it is published. It is comprehensive in that it includes uninterrupted time series from the 1950s onwards for a host of economic growth related data for 130 economies worldwide. It is also comprehensive in the sense that it includes experimental alternative estimates of GDP alongside official ones, taking into account for specific issues, for example for China’s mismeasurement of GDP and for the measurement of ICT prices in the United States.

Most importantly, TED data facilitate international comparisons in various ways. Firstly, GDP data are converted into a common currency using purchasing power parities (PPPs) from the World Bank, providing apples to apples comparisons of relative prices and levels of GDP across economies. Secondly, it harmonizes data across countries, so that for example total employment refers to all workers engaged in production, whether employees, self-employed or informal workers. In some cases it deviates from official data in order to achieve better international comparability, as is the case with hours worked in several economies including the UK. A final piece of harmonization is in the underlying methods and assumptions used in the construction of the so-called growth accounting variables. This is a well-established method to account for the sources of economic growth from a supply-side perspective, including capital, labour and TFP.

Europe’s productivity levels in comparison

As an example of TED’s possibilities, we can see how productivity levels vary across European economies. Figure 1 shows the total value added of goods and services produced (GDP) per hour worked in European countries in 2019 in comparable prices (PPP-adjusted US dollars). This year was chosen as the 2020 and 2021 productivity metrics are heavily distorted by the pandemic shutdowns – although those data can be downloaded from the TED website.

The average PPP-adjusted dollar value of goods and services produced per hour worked for Europe as whole is about 62 US dollars (PPP-converted). While this average is close to the UK, Italian and Spanish averages, the map shows that there is a lot of heterogeneity across European economies. In most of continental western and northern Europe the figures are higher at about 75 dollars or more. In economies mainly in the east and south eastern parts of Europe, but also Portugal, the average is closer to about 40 dollars per hour worked.

Which European economies are among the most productive and why? The highest level of productivity is observed for Luxembourg, which can be largely explained by its outsized financial sector relative to the overall size of this small economy. In 2019, the financial sector in Luxembourg accounted for 25 percent of its GDP, versus a 4 percent EU-wide average and 11 percent of total hours worked, versus a 2 percent EU-wide average.3 The second-best performing economy is Norway, which can again be largely explained by one relatively large and highly productive sector, which in this case is the mining sector with relatively high level of capital intensity. In 2019 this sector accounted for 19 percent of GDP in Norway versus a 3 percent EU-wide average.4 Another high performer is Ireland. In this case, the measure of GDP used for the numerator of the productivity measure may not be an appropriate measure of domestic economic activity. This is because Irish GDP figures are strongly influenced by the recorded production value from large multinational companies holding vast amounts of intellectual property, which contributes to GDP while most of the income earned over these assets flows abroad.5

Productivity growth in Europe over the last decade

How has labour productivity evolved in Europe over the last decade? First the good news. The price-adjusted value added of goods and services produced per hour worked expanded by almost 10 percent between 2008 and 2019. However, the bad news is that this represents a notable slowdown from productivity growth achieved in earlier decades, moreover progress has not been shared evenly among economies. In fact in some economies labour productivity levels in 2019 were even below those seen in 2008 (Luxembourg and Greece) or have barely grown at all (Netherlands and Italy).

Figure 2 plots the level and growth between 2008 and 2019 for individual European economies, and groups them in four categories. The upper-left quadrant consists of countries that are catching up to the European average level, as their productivity increased faster than on average, narrowing the gap in productivity levels relative to the average. This group mainly includes eastern and south-eastern economies, though interestingly also Spain. A less positive picture emerges in the lower-left quadrant, which includes economies which are falling behind on both the average European levels and growth rates of productivity. This group includes Greece, which was hard hit by the global financial crisis and the subsequent Euro Area sovereign debt crisis. The “falling behind” group also includes Italy, where lack of productivity growth is a long-standing problem—the level of labour productivity in Italy has been virtually unchanged since the mid-1990s.

The third quadrant in Figure 2 shows economies that still have productivity levels above the European average, but are losing ground as productivity growth is below the average for Europe. This group includes mostly countries in Western European accounting for the bulk of European population and GDP, including France, Germany and the UK. The last and final group consists of the countries the upper-right hand quadrant, including Denmark, Ireland, Switzerland and Sweden which are steaming ahead of both the average European productivity levels and growth rates.

The determinants of productivity growth in Europe over the last decade

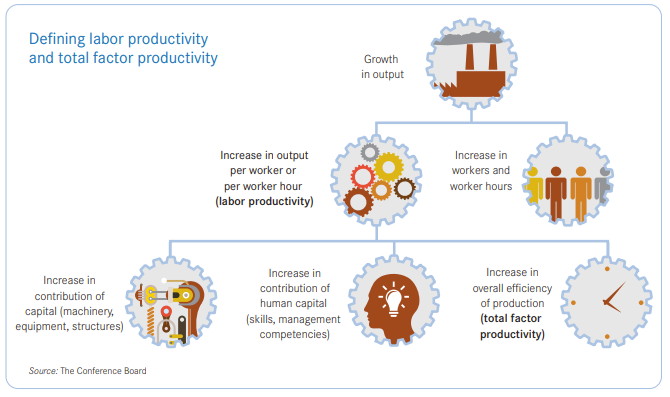

What are the driving forces behind labour productivity growth? Roughly speaking, productivity growth is determined by the contributions from the increase in the returns from capital, labour composition and total factor productivity (TFP). Capital refers to the use of machinery, equipment and structures, but also from some types of intangible capital such as software and R&D. In the TED, the capital variable is broken down into ICT capital (including hardware, communications equipment and software) and non-ICT capital (all other forms of capital expenditure). Labour composition refers to skills and competencies of the workforce, which is proxied by data on the educational attainment of the workforce. The final variable is TFP growth, which is sometimes also referred to as multifactor productivity growth to distinguish it from single factor productivity (e.g., labour productivity or capital productivity). In theory, TFP represents a measure of technological progress. More practically, it measures the overall efficiency with which capital and labour inputs are used in the production process. However, as TFP growth is not directly observed but calculated as a residual from the growth in input and the growth in income-weighted inputs (capital and labour), a large literature has developed with varying explanations of the meaning and interpretation of this variable.

Productivity definition diagram by The Conference Board

Figure 3 plots the supply-side determinants of labour productivity growth for the European economies in TED, over the period 2008-2019. Countries are grouped according to the quadrants in Figure 2. For almost all countries, the importance of increased capital deepening, that is the amount of capital used per hour worked, in driving productivity growth is notable. In the countries with above-average productivity levels (the ‘losing ground’ and ‘steaming ahead’ groups), capital deepening has in large part been driven by ICT capital while non-ICT capital deepening played a more prominent role in the economies with below average productivity levels.

The lack of TFP growth or even negative TFP growth rates is clearly visible for most European economies, except for the catching up economies. The Eastern European economies have therefore been catching up to average European productivity levels based on a combination of non-ICT capital deepening and increased TFP. For most other economies, labour productivity growth has mostly come about by expanding the amount of capital per worker-hour used in the production process.

Conclusion

This blog has highlighted the main features of the Total Economy Database, a large-scale, publicly available productivity dataset covering most economies in the world. A number of examples have been used to showcase the data and its use in understanding recent productivity dynamics in European economies.

From its early inception in the 1990s, the TED has been continuously updated and improved, taking into account the latest and best available statistical methods and underlying data. One of the unique features of the TED are the inclusion of alternative measures of output, and this is perhaps also one of the main avenues for future improvements. For example, the database includes additional series for China, based on alternative measures of output following the work of Wu (2014) and others who have argued against the reliability of official Chinese GDP data. The database also includes alternative measures of GDP for the US, following the use of alternative deflators for ICT investment goods and services based on the work of Byrne and Corrado (2016a, 2016b). Both these initiatives are important in our understanding of modern global productivity dynamics (given the size and importance of these two economies), but require follow-up research and further refinements.

Notes:

1Based on 2011 data in nominal US dollar PPP converted GDP data and 2011 population data, using the IMF World Economic Outlook April 2019 database (thereby assuming the IMF country coverage as 100 percent).

2The data can be downloaded from the TED website; For an overview of the most recent trends in a number of tables and graphs, please see our Summary Tables pdf.

3Calculated using data from Eurostat, database code nama_10_a10 for value added and nama_10_a10_e for employment. The data were downloaded in November 2022.

4Calculated using data from Eurostat, database code nama_10_10. The data were downloaded in November 2022.

5It should be noted that the Total Economy Database does not use official real GDP growth rates for Ireland. Growth rates of output (and by extensions, productivity) are based on gross value added measures which exclude sectors dominated by foreign-owned multinationals (Table FMQ01 available from the website of Central Statistics Office Ireland).

References:

Byrne, D., & Corrado, C. (2016a). ICT Prices and ICT Services: What do they tell us about productivity and technology? The Conference Board Working Paper Series.

Byrne, D., & Corrado, C. (2016a). ICT Asset Prices: Marshaling Evidence into New Measures. The Conference Board Working Paper Series.

De Vries, K. (2022a). Global Labor Productivity 2022: Stagnating, But Still Above Prepandemic Levels. The Conference Board.

De Vries, K. (2022b). Summary Tables. The Conference Board.

Erumban, A., & de Vries, K. (2022). Total Economy Database. A detailed guide to its sources and methods. The Conference Board.

Wu, H. (2014). China’s Growth and Productivity Performance Debate Revisited – Accounting for China’s Sources of Growth with a New Data Set. The Conference Board Working Paper Series.

Blog written by Klaas de Vries, and Bart van Ark

Data visualisations by Reitze Gouma